Retracing the Burke and Wills Expedition: Part 1

|

|

Time to read 7 min

|

|

Time to read 7 min

Sometimes exploring new horizons means boldly going where others have gone before.

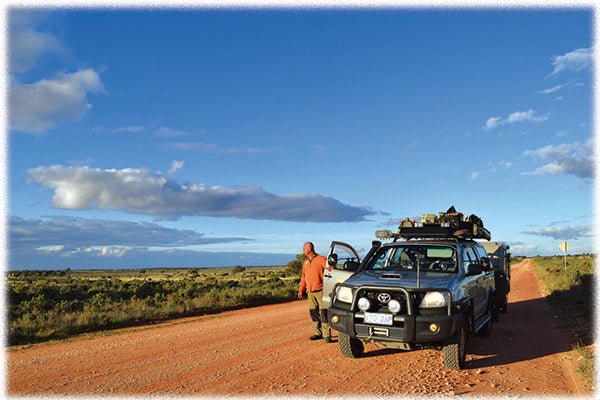

Offroad adventurers Scott and Kath Heiman have embraced this mindset with gusto, and are retracing the route of the Victorian Exploring Expedition (VEE)—better known as the Burke and Wills Expedition.

It's a 3200km journey from Melbourne to Normanton in the Gulf of Carpentaria and, while these days an overlander could drive all day in good conditions to arrive up north four or five days later, you wouldn’t see very much.

Instead, the Heimans are allowing themselves four weeks to enjoy the experience—and to get a sense of what happened 157 years ago when the VEE was sent to ‘join the dots’ between the southern and northern coasts of Australia.

The VEE planned to spend two years traversing the continent, so Kath and Scott’s journey of a month sounds like a sprint! Happily, we can be pretty confident that—with a reliable Hilux tow-tug and an Echo 4x4 Kavango camper trailer—they’ll suffer none of the deprivations of the explorers they’re following.

PREPPING FOR THE LONG HAUL

When the VEE began planning its venture into the interior, they knew the terrain would be arid and camels would be needed to deal with extended periods without food and water.

Unlike camels, we can’t expect our modern tow-tugs to simply ‘make do’ if their preferred fuel source becomes scarce. So a key part of our itinerary planning was to work out where we’d be able to fill up once we left populated areas.

While fuel consumption may be relatively straightforward to estimate for a day-to-day commute, usage increases must include the demands of towing a camper trailer over rough terrain. And it’s also important to allow for some flexibility in route selection as no one really wants to just travel from point A to point B. After all, it's a pity to ignore side tracks, byways and unexpected attractions in order to conserve 'go-juice'. And, if the going gets rough, detours of several hundred kilometres may be necessary.

Traditionally, we’ve catered for these variables by carrying extra jerry cans. But the cost has come in finding the space to carry the jerries without stuffing around with the rig’s centre of gravity or create unnecessary drag by placing them on the roof racks. So, for this trip, we took the plunge and fitted an extended long-range fuel tank to the trusty HiLux.

STRADDLING THE BUMPS

We’ve also given the 'Lux a boost in traction. The Burke and Wills route traverses environmental variations including mulga, the Channel Country, deserts and the Gulf. This terrain can be challenging and near impassable with weather changes.

We always travel with appropriate recovery gear like MAXTRAX, winches and snatch straps. But, given the number of kilometres we aim to travel this time around we figured it was sensible to install a rear diff locker to the 'Lux to reduce the likelihood of having to dig ourselves out of trouble.

The choice was simple. The ARB Air Locker is made in Australia and is known throughout the 4WD industry for its strength and durability. The five-year warranty is pretty appealing, too. Truth be known, the decision was made a couple of years ago when we installed an air compressor, purpose made for tyre inflation and locker activation.

Finally, we treated the 'Lux to a suspension upgrade. The factory rear springs were looking tired after 200,000km, including towing a camper. Previously we’d fitted OzTec’s Australian made and owned ‘Outback’ range of shock absorbers after a dramatic failure of an offshore brand. Completely happy with their performance, we fitted their mid-range 4WD and Commercial Springs – front and back.

PRECHECK ESSENTIALS

We’re not saying that you can’t tackle remote Australia without the scale of upgrades that we’ve recently installed on the 'Lux. But we conceive our big trips well ahead of time, and then save for upgrades.

Our intent is to ensure we spend as much of our precious time as possible doing what we plan to do, not hunkered down in a country town while the local repairman subjects our vehicle and camper to unexpected mechanical surgery.

Whatever approach you take, there’s no excuse for poor planning. Routine pre-travel checks and servicing are essential. Clean water, good tyres and reliable communication are also critical in remote areas. The same needs to be said for carrying spares such as the Ryco Filter 4WD service kit.

Once we’d finished thinking about the rig, it was time to consider ourselves – including our six-year-old daughter. We’re looking forward to kicking back over the next few weeks with some beers and a few old Army mates from up north, and to spending some more time in the travel books. In this way, we’ll settle on an itinerary with realistic distances and rest stops, leaving a ‘week up our sleeve’ in case our planning doesn’t align with Mother Nature’s strange sense of humour. After all, when it comes to outback travel, it doesn’t take a 19th Century explorer to understand the importance of being prepared for the unexpected.

AN UNEXPECTED STOP

On any trip away, we can expect to have a few hiccups – regardless of the quality of the trip preparation. For us, a stuffed alternator at Balranald just over the Victoria-NSW border early in our trip meant that we spent a couple more days in this location than we’d expected. So we organised replacement parts as a first priority, and then set out to enjoy the town and find out more about its place in the Burke and Wills story.

If faced with a similar setback, we don’t reckon Burke would have responded so calmly. He was impatient and this quality didn’t fit well with the task he’d been given. An expedition across the continent needed the steady-hand of a leader who had the best interests of his team, his livestock and his equipment at heart. By all accounts, Burke simply wasn’t this type of bloke.

At the very pub in Menindee where the expedition stepped beyond the brink of white settlement and into the unknown, Burke is recorded as having been ‘excitable, impulsive and headstrong’ and this view seems universal among scholars and armchair commentators alike. Burke saw himself in a race to the Gulf. There was glory to be had, and he wanted the lion’s share.

TRAVEL BUDDY DRAMAS

Travelling with a group always takes a bit of ‘settling-in’. While family and mates can be pretty easy to handle normally, when you’re with them 24/7 a bit of adjustment is inevitable.

While it can be challenging enough travelling with people we know, the VEE members probably hadn’t even met before they set off. Most of them had answered a public advert to get their jobs. And the leader, Robert O’Hara Burke, was there because he knew the right bloke. Burke was appointed at the urging of a self-interested railway contractor and landowner who was well connected in society. Burke’s credentials were limited to service as a Cavalry Officer in Europe, and a stint as the Superintendent of Police in Castlemaine.

The curator at the museum at Milparinka told us that, when a Superintendent, Burke had apparently managed to get himself lost on the road between Beechworth and Yackandandah in Victoria, just 22km away! And, according to Phoenix's book, Burke's own Expedition member Brahe reported that he “was such a bad bushman that he could not safely be trusted 300 yards away from the camp”.

So, Burke had no experience with exploring. None at all. And Wills, who ended up as the second-in-command, was a mild mannered Englishman who was selected for his scientific skills. The original 2IC was a camel handler called George Landells who resigned from the Expedition at Menindee (as did the foreman and physician) on account of Burke’s crappy leadership style.

Apart from Burke, the Expedition that left Melbourne comprised six Irishmen, five Englishmen, four Afghans, three Germans and one American. With that fiery combination, something was bound to go wrong!

RIGHT RIG FOR THE JOB

On our trip, the weather was fine and the dirt roads between Balranald and Menindee had been freshly graded, everything else was bitumen. We could have done this stint with a family sedan and a standard caravan, albeit slowly.

Back in Burke and Wills time, however, things were very, very different. The tracks, where they existed, were of extremely varied quality – and much of the time the Expedition found itself ploughing through ground that had never previously been trodden by settlers.

So the question of how to transport the party’s provisions was critical. The VEE attempted to pack more than 20 tonnes of gear for the trip, including nearly a tonne of flour, sugar, tea, coffee, salted meat, dried fruit, preserved vegetables and lime juice sufficient to support 19 men, 26 camels and 56 horses (including the draughts horses) for up to two years. And many of us have read about them taking an oak table, stools and a big Chinese gong!

So how were they going to move all this kit? One option would have been to accept an offer by Captain Francis Cadell to transport it all 800km from Adelaide to Menindee by paddle steamer – for free. But Burke refused this offer on the basis that Cadell had opposed his appointment as Expedition leader. How’s that for an indication of Burke’s headstrong character?

Instead, the work was done by camels, horses and draught horses towing covered wagons – John Wayne-style. This choice alone may have cost Burke his life – particularly when combined with the faux pas made by other Expedition members along the way.

CAMELS VERSUS HORSES

The VEE was the first occasion on which camels had been used in numbers in Australia for exploration. The only previous time was a single camel used by the explorer Horrocks in 1846. And that didn’t end well. The camel nudged Horrocks while he had a shotgun in his hand and the explorer shot himself dead!

In the earlier part of the VEE’s trip north, the relative merit of these ‘ships of the desert’ versus horses was a source of great irritation between Burke and his original 2IC, George Landells. Burke favoured horses on the basis of the speed that they could potentially cover the terrain. And they were a pretty effective choice while the Expedition covered country where waterholes were mapped or known by locals.

Landells joined the Expedition specifically to take responsibility for the wellbeing of the Expedition’s camels and had experienced their value in India. These beasts covered country like the turtle competing with the hare in the traditional kid’s story. They were slow – but they were steady. Importantly, they could operate effectively when water became scarce.