Going off-grid in Cape York

|

|

Time to read 7 min

|

|

Time to read 7 min

Back in the 1970s, when Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s shadowy state government ruled Queensland, a thriving group of people lived in off-grid bliss on Cedar Bay beach, about eight hours hard slog by foot through the rainforest from the coastal road that connects Cairns to Cooktown, just past the mouth of the Bloomfield River.

In stark contrast to the authoritative conservatism practised by Joh and his ministerial cronies, the Cedar Bay community was an alternative loose-living ‘hippy’ commune. Perhaps some enjoyed going without clothes now and then, maybe a few had a fondness for a bit of home-grown jazz woodbine and, most certainly, there was no overzealous corruptible police force cramping anyone’s style.

By 1976, Joh and his police minister had had enough of this open defiance of their heavily policed and controlled version of Queensland and so launched perhaps the most absurd police raid ever staged in Australia. More than 30 special forces officers, armed to the teeth with automatic rifles, rappelled out of helicopters and surged onto the beach aboard inflatable NAVY SEAL-style tender boats launched from a frigate anchored offshore, scattering chickens and uprooting vegie patches as they went about their business removing the contented upstarts.

Forty-one years after the raid, Joh’s long gone, but original members of the Cedar Bay hippies still live nearby, occasionally visiting their old commune stomping ground. If you visit these days, it’s possible to recognise remnants of several fruit tree orchards on flat ground behind the coconut trees and visit the marble gravestone of the commune’s sole hold-out inhabitant, Cedar Bay Bill, on the northern end of the beach. It still takes eight hours to walk there through dense rainforest. But the reward of going to the effort is, usually, having one of the world’s greatest rainforest fringed tropical beaches all to yourself.

The 70s Cedar Bay commune is quite well-known. What’s less known is that, today, there are similarly ambitious communities dotted throughout the Cape, quietly going about their business, happily anonymous, living off-grid without any real need for too much interaction with the outside world.

The weather and isolation of Cape York make it perfect for going off-grid. And really, is there any grander adventure than cutting ties with organised urbanised communities; ending reliance on supermarkets, roads, electricity, plumbing and thousands of other conveniences and opting instead to fend for yourself? All along the eastern and western coasts of Cape York there’s plenty of food in the sea, the soil is fertile and the tropical climate means anything planted grows quickly. A polytunnel, while normally used to boost humidity and heat in temperate conditions, can be used in tropical conditions to cool and regulate humidity. With a polytunnel, anyone living in the tropics can ensure a steady supply of fresh greens, which normally struggle in a hot, moist wet season.

A common misperception of going off-grid is that to do so, you break ties with community and well-grooved organised social cohesion, head off into the bush and, because there’s no infrastructure and you’re bereft of know-how, batten down the hatches and forage like a wild beast until lessons are learned and things slowly right themselves. But really, the opposite is true. Anyone who makes a serious fist of going off-grid knows the fundamental importance of a strong civic community as you make your way; planting crops, building, clearing bush, slaughtering and butchering livestock and umpteen other tasks. A tree on your property falls in a storm? — there’s likely someone nearby with a portable saw mill who’ll be willing to help cut it into timber and boards for a portion of the bounty. You fancy planting something new? — there’s bound to be someone else nearby with heaps of experience planting and cultivating exactly what it is you intend to sow.

In fact it’s exactly these type of community transactions that motivates many to seek cashless self-sufficiency in the jungle over the wage-supported supermarket-convenience of metropolitan centres.

Portland Roads, just north of Lockhart River, is a sleepy bolt hole that attracts many seeking to nourish a self-sufficient ethos within themselves to its margins. Many of the communities that flourish up there are small and malleable, almost nomad-like, with people coming and going. Some take off to go fishing on a commercial tender to earn some cash or on other similar enterprises.

Even if going off-grid ain’t your thing, spending time with people who prefer this type of life is fascinating. The work load is constant, hard and physical. In the wet, it’s baking hot and close to 100 per cent humidity by 10am, so any day’s work is best started during the cool of pre-dawn, say 4am. By 10am, if you’ve done it right, the day’s hard work is done. It’s due to this frenetic early morning activity and languid middays and afternoons that many an interloping city-dweller is mistaken into thinking that off-gridders have simply ‘gone troppo’, lost their minds and fled into the bush to escape some form of mental demon. And yet, somehow houses are self-built, land cleared for crops and animals fed and tended to. I have a mate who, seemingly, spends his time whenever I visit chilling in the shade of a mango tree, gently rocking in a hammock peering out at all around him from beneath a battered straw hat. Yet somehow, prodigious amounts of labour and enterprise happens without me noticing. Hey presto! — a two story house made out of hand milled timber appears. Lo! — a new driveway is carved through dense rainforest, graded and carefully cambered.

Years ago, a large, complete, trunk of a red cedar washed up on a deserted beach near where he lives, probably after being dislodged from the deck of a ship out at sea during a storm. That’s what he’d be thinking about in the shadows of the mango tree from 10 till 12 before lunch. Working out how he’d transport this now exceedingly rare and expensive 40-metre long tree trunk back to his property to mill and store for future building needs. It’s easy to marvel at this use of time. In comparison, I’d be pondering returning to work to fret over web banner production and addressing client concerns over copy syntax disagreements.

Getting the trunk off the beach wasn’t easy. He had to wait many months for a king tide and favourable currents, rope in eight blokes, take them in his tinny with 25hp outboard to the beach where the trunk languished on the high-water mark, jumbled up with single rubber thongs, barnacle-encrusted bottles and other flotsam, chain the trunk to the back transom, then float, push, cajole and wrestle the trunk so it ended up floating behind the tinny. Then he towed the massive log, inch by inch, metre by metre back to a wharf serviced by a dirt road in the mouth of a nearby river.

Today, he has a house in the rainforest with red cedar benches everywhere and perhaps the most magnificent dining table I’ve ever seen.

Going off-grid pretty much ensures every day is an adventure. Opportunities present themselves like logs off a ship, but to grasp the moments — and when you’re fending for yourself you must grasp every moment — a solid community foundation is literally what separates life from death.

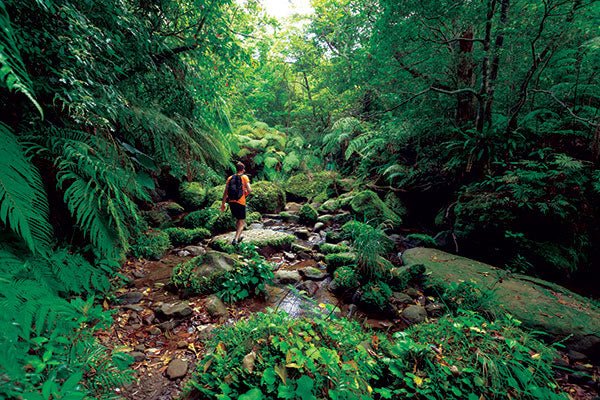

The distinctive pointed tip of north east Australia is almost entirely unoccupied. There’s a central road that connects Cooktown and Laura at its southerly base to Bamaga at its apex. In between is a mixture of tropical jungle, especially in the south around the Bloomfield River, and scrubby inland tundra and open country. There’s also multiple large river systems that deal with the monsoonal deluge and, as there’s not much in the way of highlands, quite a bit of meandering marine swampland.

Going off-grid is a community affair — unless you’re extremely jacked with the whole thing and want to go on a Man Friday-style trip and completely isolate yourself from humanity and bash it out on your own, masochistically, without any outside help. Cape York accommodates both off-grid extremes and everything in-between.

Whatever style you choose, a monumental amount of pre-move preparation is mandatory. Before embarking on a complete alteration of method in sustaining one’s self and perhaps, your family’s, a total self-diagnosis on skills, shortcomings and capabilities is required. Are you cut from the right cloth? And if not, what will it take to get you there? The tropics is an unforgiving and relentless environment, not at all like the tropical paradise myth routinely trotted out in magazines and brochures. A simple nick, or even a scratched mossie bite, on the arm or leg can quickly get infected and turn into debilitating never-healing ulcers. A sound medical check-up before embarking on your new-found life is essential. A clear understanding of your health, what your body can and can’t cope with (everyone’s different) will give you a sound perspective on types of food you need to eat and other types of sustaining habits you should practise.

Power and water supply is, of course, paramount. Many off-gridders use reticulated poly pipe set in a nearby watercourse above their living quarters and then let gravity do its work. Simple and effective. A looped coil on the roof in the sun is a good way to ensure at least one hot shower to start the day.

Multiple renewable energy power sources are usually employed by off gridders. Solar panels, water turbines set up in nearby water courses with regular current, gas-powered fridges, windmills. Power becomes a scarce commodity and many quickly learn to conserve and use it judiciously. You'll have to, too.

Check out the full feature in issue #121 of Camper Trailer Australia magazine. Subscribe today for all the latest camper trailer news, reviews and travel inspiration.