Discovering the Secrets of Uluru

|

|

Time to read 3 min

|

|

Time to read 3 min

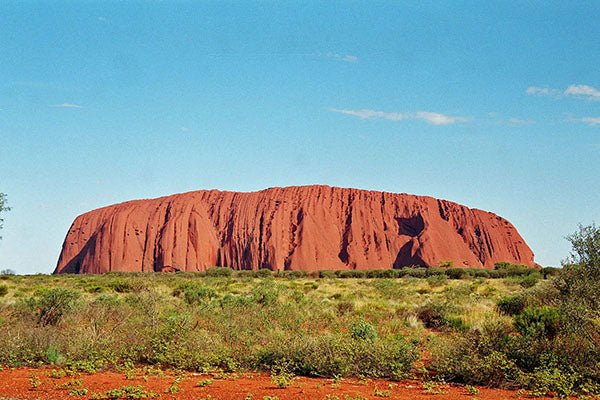

Uluru is arguably one of Australia’s most iconic views. The Rock, as it’s affectionately known, rises an impressive 348m (1142ft) from the sandy desert plain in the Northern Territory.

It’s often described as “the largest monolith in the world,” which suggests it’s a single rock, but this belies the true nature of its formation. Uluru is composed of a coarse sandstone, known to geologists as an arkose. It was formed from sediment washed down from a high mountain range to the south and west into an alluvial fan about 500-530 million years ago. The coarse nature of the grains, i.e. the absence of ‘rounding’ and the lack of sorting into grain size indicate they eroded rapidly from a granite rock and had not been carried far before being dropped.

This blanket of arkose was at least 2400m (7900ft) thick when it fell, and what we see today as Uluru is an eroded remnant of this layer, which was twisted upwards to an almost vertical form between 400 and 300 million years ago during a period of mountain building. Surprisingly, there are relatively few fractures, jointing or major bedding structures in the uniform rock which forms Uluru, which is why it has been resistant to erosion. This is why there are no erosional scree slopes or soil around its edges, which gives it the appearance of sitting on the surrounding landscape, much as a pebble might sit on a beach.

The local Aboriginal population considers Uluru as sacred and explains its origins in the Dreamtime. Archaeological work in the area indicates that Indigenous inhabitants existed here more than 10,000 years ago, when the landscape would have had much the same appearance as it does today.

The first European to see it was William Gosse in 1873. The surveyor and explorer named it Ayers Rock in honour of the former Premier of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. At the time Gosse wrote: “It is certainly the most wonderful natural feature I have ever seen.”

In 1993, the Northern Territory government assigned it the dual name Uluru/Ayers Rock, when the local Pitjantjatjara title of Uluru was applied and it now sits in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, where it is closely overseen by Indigenous rangers.

In the earlier days of mass tourism to the Rock it was customary to climb to the top but this is now considered disrespectful (although not banned). The rock pools, which form readily around the base of the Rock were a source of life and the many paintings indicate the richness of the area for the original inhabitants of the area.

While the flora has changed little over the past 200 years, fauna fared poorly with only 21 species of 46 identified remaining due to an influx of pest species.

Although flat, walking the 10km base is a test of endurance in the hotter months. If you go – and you should – join the crowd at the viewing sites to watch The Rock change colour at sunrise and sunset.

A LONG WAY FROM ANYWHERE

Located 335km south west of Alice Springs, Uluru was still quite a remote and difficult to reach location, even for travellers in the 1950s. In the early 1930s there weren’t even tracks leading into the region.

A trip in the early 1950s involved a two-day bus journey which could easily have required all passengers to exit the bus and help push it through heavy sand or other difficulties, and tourist buses not uncommonly got lost.

The owners of the Curtin Springs station – now mainly known as a stopover point and camping ground along the Lasseter Highway leading to Uluru – frequently had to undertake rescue missions to locate and retrieve missing parties of travellers.

Today, a modern sealed road takes you right to the resort and the foot of the rock and you could leave Alice Springs after breakfast and be there for lunch.

DO IT FROM HOME

It’s nowhere near as much fun, and the atmosphere isn’t the same, but now you can enjoy the Uluru experience at home via Google Street View.

You can zoom in or out of rock crevices, check out the rock art, follow local trails and visit waterholes, but, as with foot-bound tourists, the sacred areas are bypassed to keep you from encroaching on sensitive locations.

The Street View coverage of The Rock is the result of two years of work and negotiations with the local Aboriginal caretakers. Google says it expects that this will not decrease tourism to the area, and, based on its experience with major public area coverage overseas will result in increased public interest.